Photos by MOTOKO

ー

What kind of research are you conducting in your laboratory here in the Faculty of Agriculture at the University of Tokyo’s Yayoi Campus?

Dr. Igarashi

In a nutshell, this research is about replacing all chemical reactions with enzymes. Although the chemical industry is an essential part of the foundation of our everyday lives, it has always consumed too much energy and materials. The question is, how can we derive the same benefits in a more biological way? Organisms have the ability to put things in motion quite exquisitely, and they owe this ability to their enzymes.

Wow, high praise. What a great way to start!

ー

By “ability to put things in motion,” are you referring to the degradation and bonding that occur in the context of enzymatic reactions?

Dr. Igarashi

“Degradation” sounds fairly technical, but yes. For example, humans use digestive enzymes to break down the starch they eat. We can do this because we have degrading enzymes in our body that can convert starch into nutrients. On the other hand, the reason we don’t eat trees for nourishment is because we do not have degrading enzymes that can break down trees.

ー

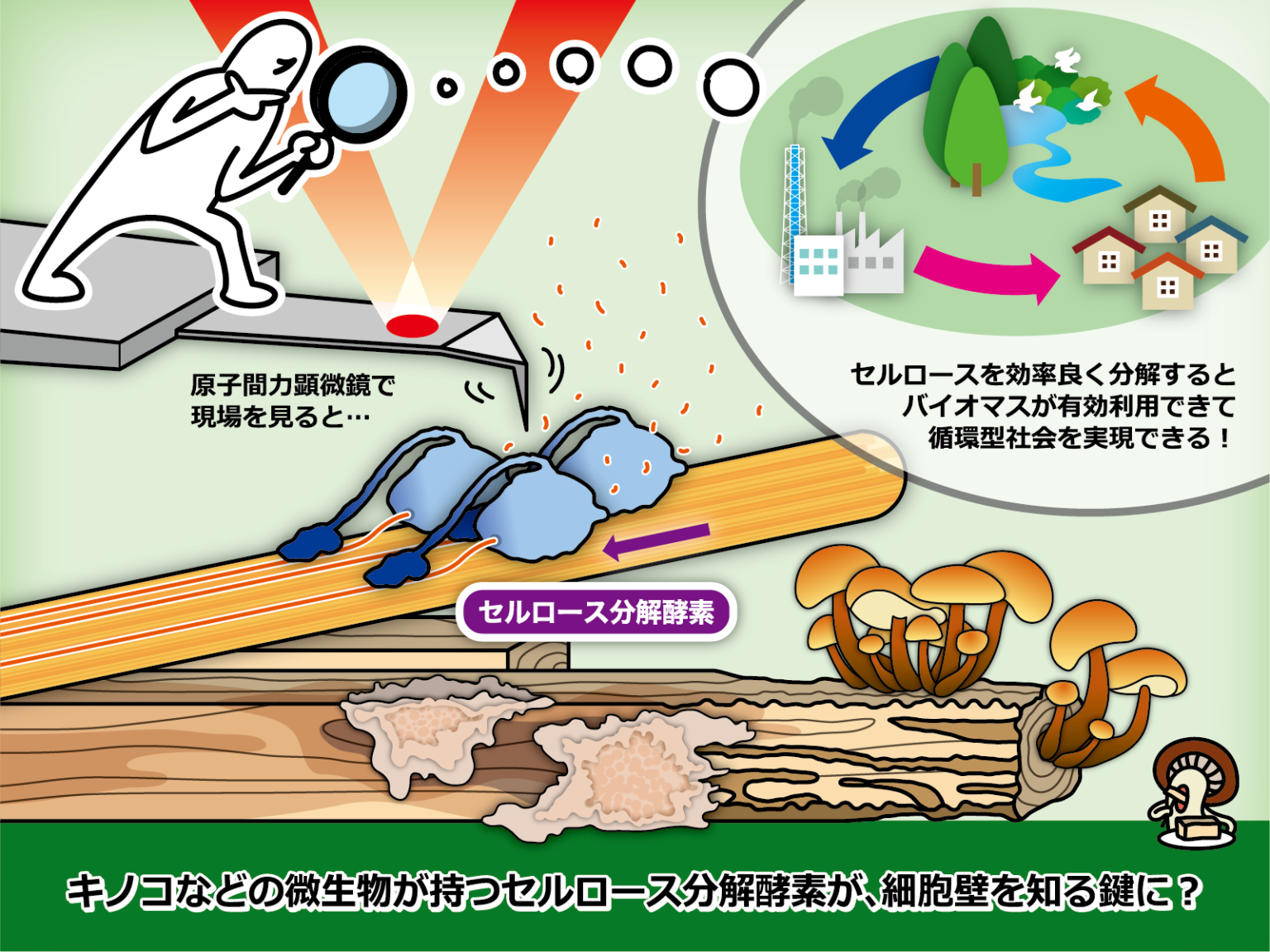

For us to utilize biomass—non-fossil biological resources—we must first break it down.

Dr. Igarashi

That’s right. In our laboratory, we’re looking to biologically transform biomass into new resources for us to use. We need degrading enzymes to convert biomass into various products. We’re studying the best ways to use these enzymes, which is how we ended up focusing on the enzymes produced by mushrooms.

Mushrooms use a lot of enzymes to break things down.

Dr. Igarashi

When I was in the forestry department at the University of Tokyo, I was astonished by what we found in our research. We conducted an experiment to grow mushrooms in sawdust. Not long after inoculation, mushrooms sprang out of the sawdust. Mushrooms will eat anything you throw at them, from sawdust to disposable chopsticks, toothpicks, newspaper, and more. They break it down in a week or so and use it as their energy source. I was taken aback by their voracious appetite, and at this staggering mechanism.

Without us, biomass would just sit there for hundreds or maybe even thousands of years. Mushrooms are amazing—with us, they can break all that down and eat it right away!

ー

What made you start studying biomass?

Dr. Igarashi

I study biomass because at some point in the future, we will no longer be able to use oil, coal, and other fossil resources. Because whenever we burn them, CO2 is emitted. Fossil resources are created from the remains of animals and plants over hundreds of millions of years, as you know. If we didn’t dig them out of the soil, the CO2 they stored wouldn’t be up here on the surface of the earth.

We learned a lot about how enzymes create fossil resources in the Enzyme Talk with Dr. Fujii, the soil scientist.

Dr. Igarashi

Photosynthesis is what reduces the concentration of the CO2 we dig up and release. So, humans should only emit as much CO2 as plants can absorb. That is the essence of the concept of carbon neutrality.

In the future, with very few exceptions, humans will probably be prohibited from using fossil resources. For example, now we can buy a liter of gasoline for a few hundred yen, but should it really be that cheap? Many countries are considering carbon taxes and other types of taxes on fossil resources. According to my calculations, if we add those, the price of gasoline should increase to 300 or 400 yen per liter.

Are you serious?!

Dr. Igarashi

When that time comes, it won’t be just gasoline—all energy will be extremely expensive. At some point, we will have to completely rethink how our society is structured. For example, now we talk about reusing things and extending the lives of products. We’ll need more of that kind of thing.

ー

For that, we use terms like “energy conservation” and “circular economy.”

Dr. Igarashi

In a few hundred years, we are using up what took hundreds of millions of years to accumulate. This means we’re using it a million times faster than it is being created. If we continue to consume energy and materials at this rate, we will ruin the earth, one way or another.

Does that mean we’ll see tremendous environmental changes on the same level as large meteorites hitting the earth or major volcanic eruptions millions and billions of years ago?

Dr. Igarashi

We just might. How many people realize that we are already on that path? When we think about the future, the best thing we can do is to stop living in a way that produces more CO2.

ー

What specific resources do you think we can use instead of fossil resources?

Dr. Igarashi

We can use the organic matter around us on the earth right now. But we can’t use rice, wheat, or potatoes. If we do, we’ll run out of food when the population increases.

We need to use resources we have never used before. We use scraps of wood from building materials and the paper manufacturing process. We also use grasses and other herbage. The easiest to use are bagasse—the pulpy fibers that remain after crushing sugarcane—and rice straw. If we can turn these things into resources, we can reduce the amount of oil we consume.

(Direction: Mitsuko Kudo, Illustration: Hiroko Uchida)

ー

How much of these untapped natural resources exist right now?

Dr. Igarashi

There are tens of millions of tons in Japan alone. For example, right now, Japan uses about 10 million tons of plastic per year. We need to replace around 20% of that with something else by 2030. We can’t do that without using millions of tons of some untapped natural resources.

Fortunately, we have vast quantities of used paper, and there are also millions of tons of branches, roots, and other forest-thinning waste sitting in our forests. However, we have a lot of work to do to make it truly available to us. That is why we are researching how to use enzymes.

So, the natural resources exist. And we have our work cut out for us. But we can only work so fast . . .

Dr. Igarashi

No matter how hard we try, I think we can only increase enzyme activity by 10% or 20%. After that, the question will be how efficiently we can make it happen and how much time we can spend.

Eventually, humans will have to adjust to the speed of nature. We will create a system that allows for proper conversion without using more energy, even if it is slow. If we undertake this task in earnest, I think the time will come when we can harness the power of enzymes.

That’s the kind of time it takes to make the necessary changes in human society. You don’t need to wait hundreds of millions of years until natural resources are ready in order to use them, but it is super important to realize that you’re using things it took nature hundreds of millions of years to make.

Dr. Igarashi

When I started this research, people made fun of me for saying that I would use enzymes to solve this problem. It was inconceivable at the time that enzymes would garner the attention they have today.

According to researchers at Amano Enzyme, long ago, the main focus of biotechnology and enzymes was food and pharmaceuticals, but now the scope has expanded to the point of asking what biotechnology and enzymes can do in every field.

Dr. Igarashi

The current challenge in using biomass is its high price. Of course, it will be expensive. After all, oil and coal are so cheap because they were created naturally a long time ago.

ー

You’re saying that humankind is eating into the legacy of the past.

Dr. Igarashi

Correct. We use materials that put such a burden on the earth, but give nothing back. In this day and age, we have the concept of fair trade.

You mean the system that ensures that the people who sew our clothes and grow the cacao for our chocolate get their fair share of the money!

Dr. Igarashi

That’s the one. A carbon tax operates under the same concept. Our actions tax the earth, so we should use a commensurate amount of money to restore it. If we do that, there will soon come a time when nothing is as expensive as coal or oil.

People only say that biomass is expensive now, but I think it will be the cheaper option in the future. It is already around one-tenth the cost of what it was when we started our research. With continued research, I think we can reduce the cost even more.

Fossil fuels are like the earth’s savings. On the other hand, biomass is like income. Of course, it would be easier if you could rely on your savings . . .

Dr. Igarashi

We will run out sooner or later.

ー

Dr. Igarashi, you studied in Finland for a time. Did you notice any differences in research between Finland and Japan?

Dr. Igarashi

I feel like researchers in each country have a different stance altogether. In Finland, junior high school students learn at about the same level as high school students in Japan. Biology is no different, and the overwhelming majority of students go on to study biology.

Their way of life is different as well. For example, they have an extremely well-considered way of disposing of waste in an effort to become a bioeconomy—that is, a society that uses biomass and biotechnology to avoid burdening the biosphere. They grow up in a society where that is the norm.

(Source: https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/focus/ja/features/z0405_00019.html)

ー

When we think of education in Japan, we mainly learn what is written in textbooks, and we may not see how much of it relates to real life.

But living things are so much a part of our lives! Maybe we should teach that way in Japan. This is really deep, if you think about it.

Dr. Igarashi

In Finland, people believe that everything is connected to nature. For example, garbage is actually a familiar part of nature. Under their carefully thought-out system, they realize that everything they eat and throw away goes somewhere on the earth. In Japan, people seem to think that throwing something into a trash can means it’s gone, but that is not really the case.

I heard that Finnish people view poisonous mushrooms as not merely poison, but as a resource with toxins that can be used as ingredients in pharmaceuticals and other products. They learned how to use the nature around them, which did not have a whole lot of resources despite there being so many forests.

Dr. Igarashi

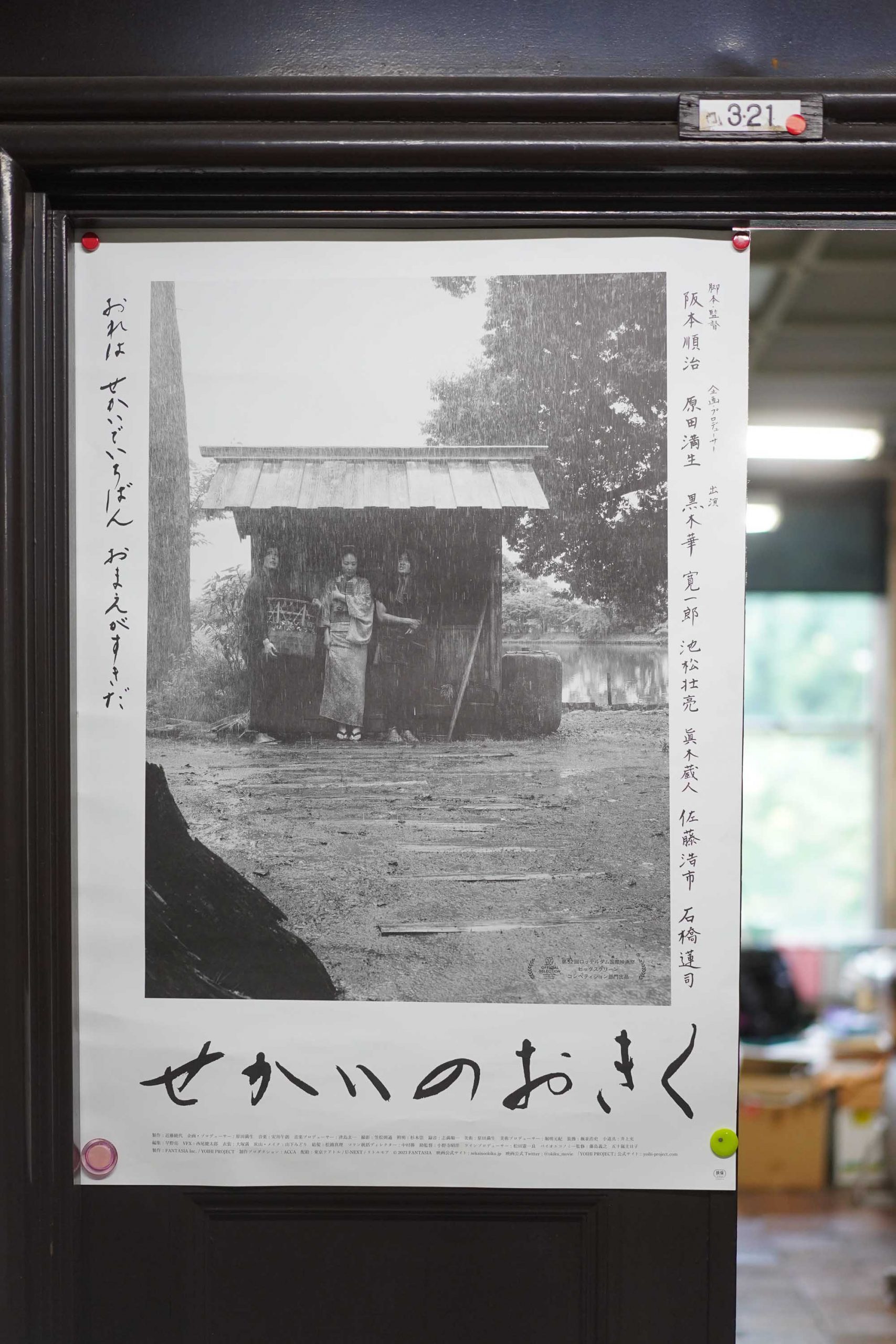

You know, I also work as a film supervisor. I recently supervised the bioeconomy of a film called Okiku and the World. It made me realize that, long ago, Japan was like how Finland is now. Until around 150 years ago, everyone lived the way they do in Finland now, including the common people. As is the case everywhere in the developed world, at some point, it seems that we forgot how to live that way.

Somewhere along the way, people in Japan left that kind of thinking behind. But I feel like young people, especially, are beginning to take an interest in the wisdom of the past again. The same is true of the recent fermentation craze we learned about in the Enzyme Talk with Hiraku Ogura.

Dr. Igarashi

You know, I have some wilderness of my own at my house.

What do you mean by that?

Dr. Igarashi

Two-thirds of my property is forested, and I live in a house on the remaining third. I decided to do that because about 70% of Japan is covered with forests. So, the ratio on my land is the same. The idea is that if I can create a bioeconomy and live a recycling-oriented life in my home environment, it can be done everywhere in Japan.

People in Tokyo and other big cities may disagree, but I think they feel as though nature is something “other” and unrelated to them. But just like garbage in Finland, it is better to have a sense that your own life and nature are connected. So I see more opportunities in the future in places like smaller cities.

Modern society thrived on the development of petrochemistry, but it is turning a corner now. From now on, we will use enzymes to turn biomass into a new resource. Dr. Igarashi not only conducts the research, but also lives a lifestyle that harnesses the power of nature. In Part 2 of the interview, I asked him about the details of his research and how he plans to apply the results in industrial settings. Also, look out for a 3D model of Enzo!

→ Continue to Part 2Enzymes are active in every aspect of our world, and we are seeking new possibilities for them.

In this corner, we visit people who are currently active in various fields with "Enzo" and ask them about their stories.