Photos by Tsunaki Kuwashima (KAIBUTSU)

ー

That’s a very stylish hat you are wearing, professor.

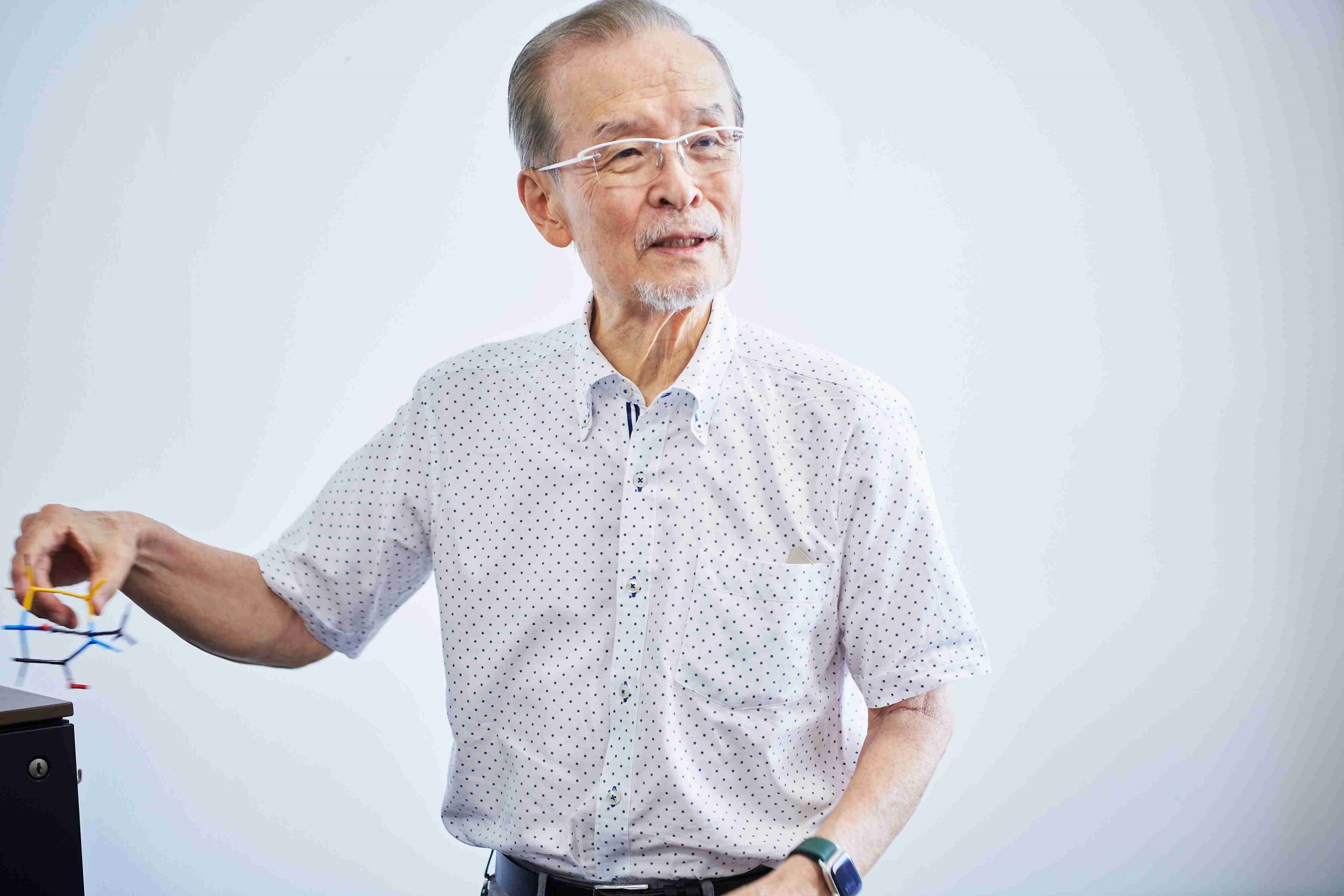

Dr. Yamamoto

Dr. Yamamoto: I have about seven or eight hats for each season. I wear hats to protect my head. I’m 81 years old. And I would like to keep working for at least four more years.

ー

I notice that your room here at Chubu University has no bookshelves. It’s a very minimalist space. Is this how you normally like it?

Dr. Yamamoto

Dr. Yamamoto: Yes. After finishing the books I read, I get rid of them. Even when I receive a commemorative photo of myself, I throw it in the trash after taking a good look at it. I’ve already seen enough photos of myself in my life.

Enzo: That’s amazing! Not only do you practice “decluttering,” you don’t even keep any stuff at all!

Dr. Yamamoto

Without that kind of attitude, I don’t think you can create anything totally new.

ー

You are known as a leader in acid catalyst research, both in Japan and internationally, but in recent years you have focused on peptide synthesis. Why did you decide to take on the challenges of a new research field from scratch?

Dr. Yamamoto

Most of my life as a chemist, which has spanned more than half a century, has been devoted to pure research (the core of applied research). I found it interesting and fulfilling, and I became famous in my field.

For example, for key terms like “Lewis acid,” “Chiral Lewis acid,” and “Brønsted acid catalyst,” my papers are apparently the most cited in the world. But it’s not an achievement that is particularly pleasing. That kind of work doesn’t directly help people in any way.

You mentioned research on what you call “asymmetric reactions.” They contribute to the development of various new chemical substances and play a vital role in the manufacture of pharmaceuticals and industrial materials. So, it’s not true that this kind of research is not valuable to society…

Dr. Yamamoto

Maybe it will become very useful 50 years from now. But that won’t matter to me. That kind of research is not shaping today’s world. I was over 70 when this realization hit me.

Was there any particular event that was a turning point?

Dr. Yamamoto

I was thinking about a certain scientific conference at the end of the 20th century. The World Conference on Science in 1999, held in Budapest, the capital of Hungary. Around 2,000 scientists from all over the world assembled to discuss one question, “What kind of science and technology does the world need for the next century?”

At this conference, the “Budapest Declaration” was released. It says that science and technology need to change, to become more useful to humans. Since then, science and technology projects in Europe and the U.S. have gradually focused more on things that are helpful to people. This trend is barely evident in Japan, however. I am guilty too, because I had a similar attitude until I turned 70.

ー

Are you saying that Japanese researchers still live in an ivory tower?

Dr. Yamamoto

Yes. I spent about two years thinking, “What should I research next?” That’s when I decided to abandon all my previous research to focus on peptides.

ー

This was when you returned to Japan after working as a professor at the University of Chicago for around 10 years, when you moved to Chubu University.

Dr. Yamamoto

In the U.S., I felt that my career as a researcher was just about complete, but I felt like doing something more. I wanted, if possible, to do work that would be directly useful to people.

That’s a big commitment, professor, but it’s typical of your desire to constantly explore new things.

Dr. Yamamoto

It wasn’t like I was starting a totally new kind of job at the age of 70 plus. But I did come up with a method of creating peptides that no one had ever thought of.

Dr. Yamamoto

Some 2,000 to 3,000 kinds of naturally occurring peptides have been classified, but that is only a tiny fraction of all peptides. Consider peptides made of 10 amino acids connected together. Since 10 amino acids can be combined in countless different ways, there are roughly 10 trillion possible peptides. Within proteins, countless peptides that are equivalent to enzymes are found by chance. So, we have unlimited possibilities to explore in this field.

Enzymes and peptides are similar. Both are made of amino acids and help to activate various chemical reactions in the body. The main job of enzymes is to promote and accelerate reactions. Since they convey specific messages in the body and play a role in growth and health, peptides are considered particularly useful in drug discovery.

Dr. Yamamoto

Correct! But, out of 10 trillion peptides, only about 1,000 peptides have been turned into drugs, through chance discovery. Until now, drug discovery has relied almost entirely on chance. That’s true for both traditional herbal and Western medicines.

But what if we could design new peptides from scratch? That would be totally revolutionary!

That sounds a bit like how antibiotics are made.

Dr. Yamamoto

All medicines except for antibiotics are invented more or less by chance, with a probability of say 1 in 10,000. It would surely be wonderful if they could be designed according to specific goals, like antibiotics?

I’ve heard that the number of peptides that are being discovered is gradually decreasing, so there will probably be strong demand for the new method you devised.

Dr. Yamamoto

There are two kinds of science; the science of certainty and the science of chance. In the science of certainty, you work methodically and keep examining how well what you are doing conforms to certain rules. That’s how physics works. In the science of chance, you try something different every day, hoping that one day you hit upon a useful discovery.

ー

That means that chemistry is basically a science of chance.

Dr. Yamamoto

Right! I was OK with this. In fact, I quite liked that approach. I never thought there was anything wrong with it. But now, I want to work in a logical way to make new discoveries.

ー

How do you go about synthesizing new peptides?

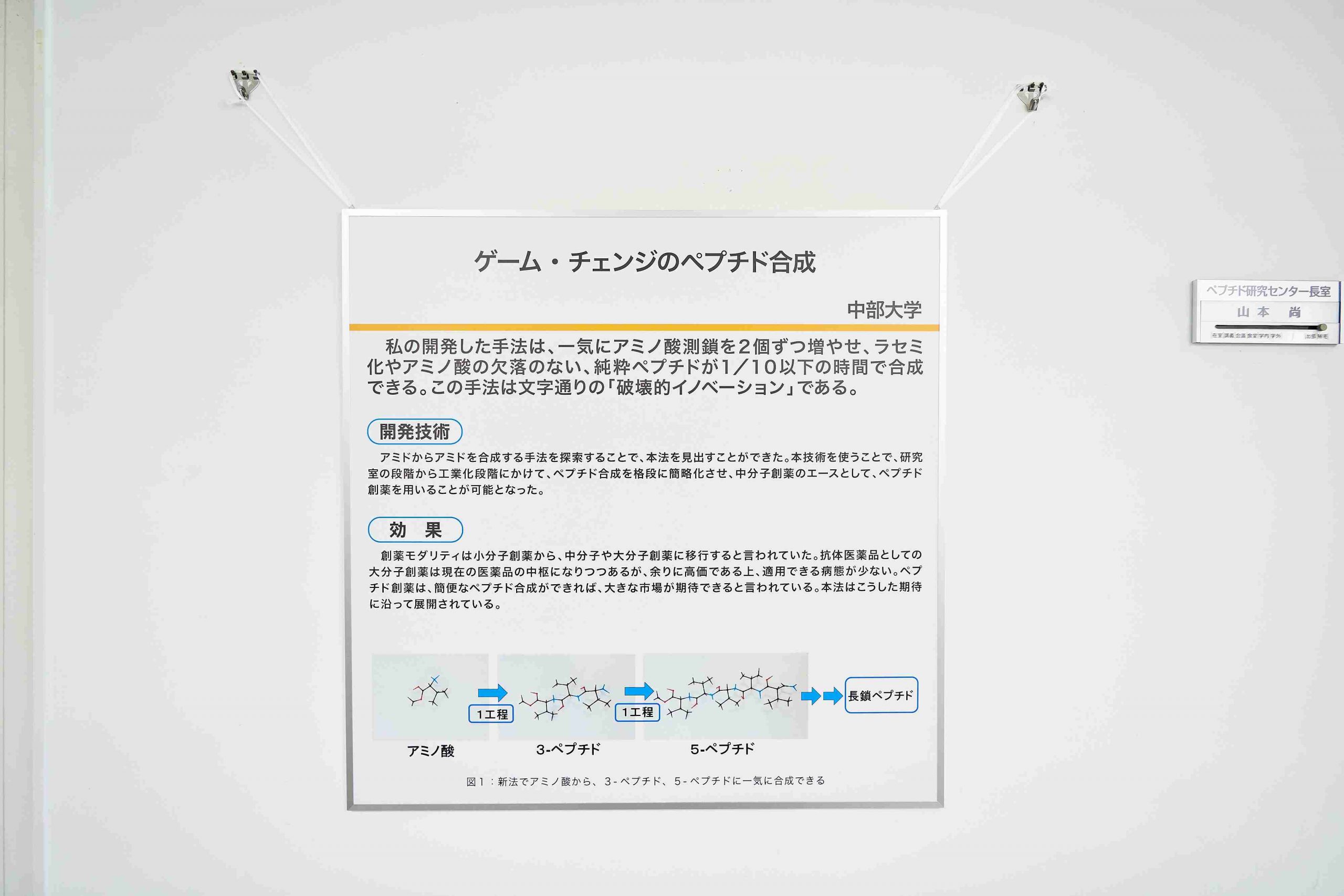

Dr. Yamamoto

First, you add a certain compound to a peptide or amino acids. This forms a tripeptide, made up of three amino acids connected together. If you do the same thing again, you end up with five amino acids connected together.

Dr. Yamamoto

Like this, you can keep expanding rapidly. Even the best labs used to take more than a year to produce a peptide with 20 to 30 amino acids. The process was very difficult. But with my approach, it takes only two weeks.

Wow! That’s much faster.

Dr. Yamamoto

Yes, it’s impressive, isn’t? On one plate you can have 20 times 20, i.e., 400 different compounds called diketopiperazines, to which you add another amino acid. Then you will have one amino acid connecting to two, separate amino acids. We can then pick the best ones from there. If you then repeat the process 20 times, you end up with 8,000 different tripeptides.

Dr. Yamamoto

This work is done mechanically using robots in a process that combines mechanical engineering and organic chemistry. It’s a wonderful method, but the extremely high cost of the machine presents a bottleneck (wry smile). Although it’s only about a meter and a half in size, it costs more than ¥100 million.

Do you already have one in your lab at Chubu University?

Dr. Yamamoto

No, but the Next Generation Peptide Research and Development Center of the Chiba Institute of Technology, where I have been working concurrently since the spring, has purchased one. It is due to be delivered in about six months. Many companies around the world are trying to get their hands on one of the machines, which are made in Switzerland, so they are not easy to get. The current delivery waiting time is 1.5 to 2 years from order.

The researchers at Amano Enzyme are also using machines to search for enzymes. They prepare a “library” of microorganisms as a base for screening. Without knowing when they will find what they are looking for, they stick to the task intently. People say that Japanese researchers are particularly suited to this kind of steady but difficult work.

ー

I was wondering why your method was not attempted before now? Was it necessary to wait for a machine like this to be developed?

Dr. Yamamoto

Yes, partly. But even if the machine was available, it would have been impossible without my particular approach and method.

ー

When did you devise your technique and when did it get published in a paper?

Dr. Yamamoto

It was about two years ago. I currently refer to the technique as “two by two.”

It is genuinely cutting-edge research!

ー

So, we have now arrived at the point where we can make discoveries that previously could only be made by chance in a much faster, logical, and efficient way.

Dr. Yamamoto

That’s right. The point is that in chemistry, discoveries are based largely on chance, but machines are based on logic and certainty. It has been difficult to link chance-based research with machines, but it needs to be done. The skillful use of machines will become increasingly important.

From science of chance to science of certainty. With a simple idea that no one had ever thought of, Dr. Yamamoto has cut open a new path in peptide synthesis. In the second part of the interview, he shares his thoughts on where creativity comes from. He also recounts a childhood episode that inspired him to become a chemist and offers a message to students and young researchers. We also ask him about the kind of research that makes best use of Japan’s unique characteristics, a subject he has reflected on at length during his many years of research overseas.

Continue to Part 2Enzymes are active in every aspect of our world, and we are seeking new possibilities for them.

In this corner, we visit people who are currently active in various fields with "Enzo" and ask them about their stories.