Text by Hirokuni Kanki

Photos courtesy of JAMSTEC

ー

Doctor Takai, you have been looking for hints about the origin of life in your research on deep-sea hydrothermal systems. What inspired you to become a researcher?

Mr. Takai

I decided to be a researcher because I wanted to do something that I could be the “the best in the world” at. When I was accepted to Kyoto University to study fisheries in the Faculty of Agriculture, I was already aiming to win the Nobel Prize.

You were very ambitious since your high school days…!

Mr. Takai

Yes, I always had big ambitions (laughs). I chose to specialize in microbiology at Kyoto University so that I could focus on molecular biology, a field that was getting a lot of attention at the time. My advisor offered me two research options. I could either study the genes that produce toxins, or hyperthermophiles, which are organisms that live in hot springs and hydrothermal systems in the deep sea. “Which one would you like?,” he asked.

I was unsure, so I consulted a friend. He told me, “Hyperthermophiles are more exciting, because they're connected to the origin of life. It’s an even bigger deal than the Nobel Prize.” So, I committed myself to tackling the challenges of the deep sea, driven by a desire to be the first person to penetrate the mystery of life’s origin.

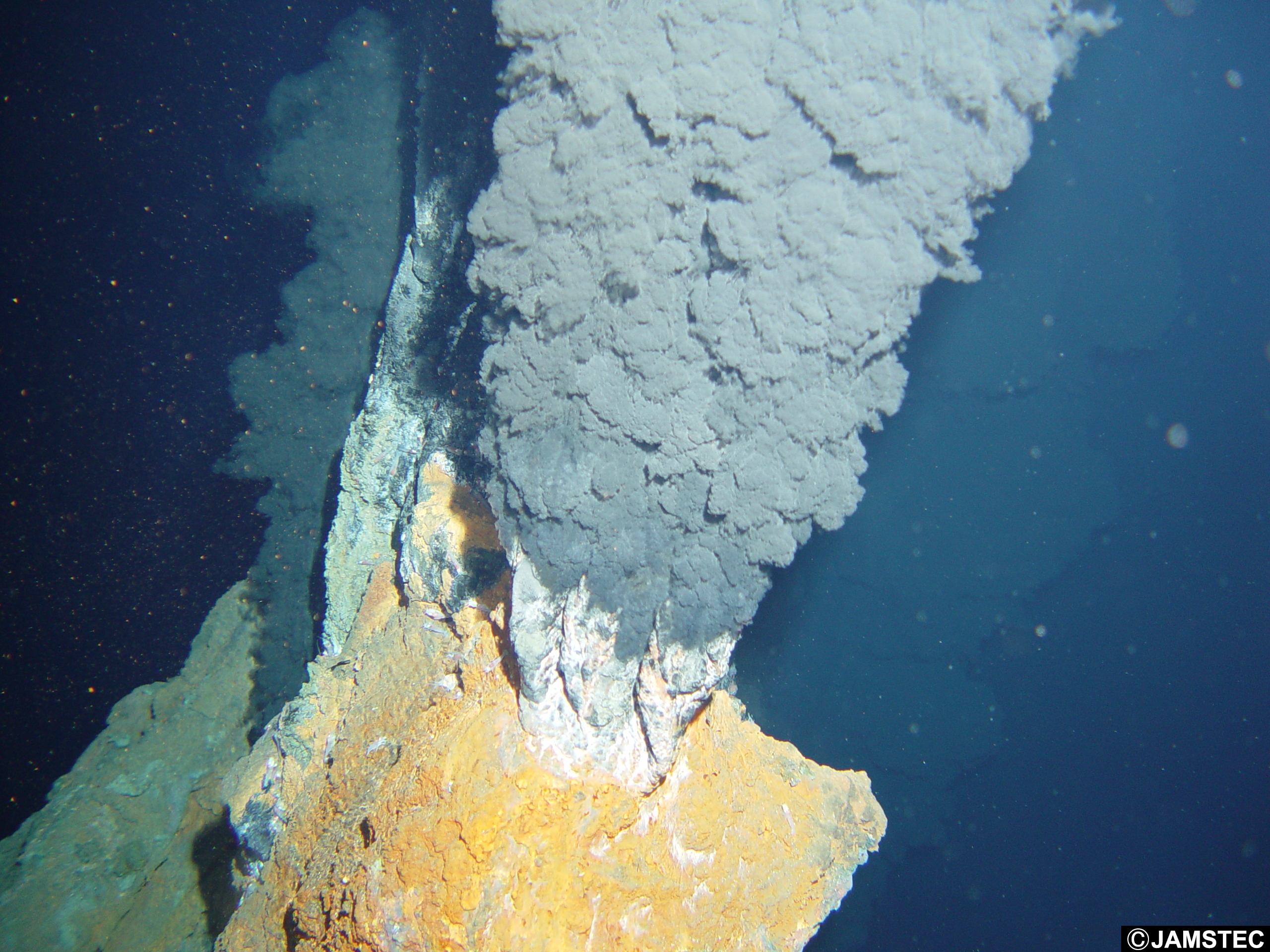

I once saw a picture of a sea-floor chimney (hydrothermal vent) in a science magazine. I was surprised to see so much colorful life at the bottom of the sea.

©︎ JAMSTEC

Mr. Takai

It was a long time after I became a researcher that I started to love the ocean. At first, my mind was more occupied with collecting the samples I needed than on enjoying the sea, so the pleasure of diving totally escaped me. “Let’s just grab what we need and get out of here as soon as possible.” That was my attitude. I found the environment quite frightening.

ー

You are doing your research at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC). How is the agency structured?

Mr. Takai

At JAMSTEC, I head the Institute for Extra-cutting-edge Science and Technology Avant-garde Research (X-star). As our name suggests, we do extremely cutting-edge research (laughs).

ー

Why are you so committed to manned exploration?

Mr. Takai

Of the three basic approaches to science—theory, experiment, and observation—my main focus is observational science. I believe that intuition is the driving force of science. That’s why I cannot trust researchers who don’t get out into the field to develop their intuition. I believe that the experience of seeing things directly and the sense of realness that you get in the field is the main driver of life as well as science. So, that is what I want to contribute now. This is the quickest and simplest way to cut through reality and gain insight. And that’s how I’ve got to where I am today, I think.

©︎ JAMSTEC

What is it like to experience the deep-sea world so directly?

Mr. Takai

Deep in the sea there are places that appear to spring up like Las Vegas emerging suddenly from the desert, with huge skyscraper-like formations of marine organisms. There are hydrothermal vents emitting energy in the form of hot water. Chimneys collapse, only to immediately take shape again. Life arises, gets destroyed, then arises again, over and over. When you see all this directly, you intuitively understand that with its never-ending supply of energy, such a world must be habitable. That is, you get a sense that there must be organisms living in the environment.

ー

I understand that you spent some time studying enzymes when you were younger.

Mr. Takai

Before submitting my doctoral thesis at Kyoto University, I studied the thermal stability of certain enzymes. Enzymes typically function at around human body temperature. That’s because they are designed to work at the temperatures at which the organism is most active. PCR tests take advantage of this property, for example.

That’s how enzymes can be useful. However, for more than 50 years, protein researchers have been struggling to understand the essential question of why enzymes break down, or don’t break down? Once their gene sequence is determined, the thermal stability of enzymes is fixed. For example, with the right genetic sequence, you could create eggs that don’t transform into boiled eggs, regardless of how much you heat them.

I’m glad you brought up the relationship between temperature and enzymes!

Mr. Takai

To understand the rules of this relationship, the best subject is a class of organisms known as “hyperthermophiles.” I wanted to study them to solve this mystery of enzymes. However, when I was doing my PhD, structural analysis came into widespread use all over the world, so the mystery was gradually cleared up. I had wanted to solve the problem, but other people got there before me. “Damn!” I thought to myself. “I need to quickly find something else to tackle.”

I heard that there was a big shift in molecular biology from the late 80s and into the 90s. Finding gene sequences became commonplace in the 90s.

Mr. Takai

That was definitely the heyday of biotechnological cloning, but in the world of microorganisms, things moved more slowly. Methods for examining environmental DNA directly, which we now call metagenomic analysis, finally began to emerge. I thought that if I used such tools to investigate hot springs and deep-sea hydrothermal systems, I should be able to find ancient microorganisms that no one had previously discovered. And for that kind of research, JAMSTEC was the best place to be.

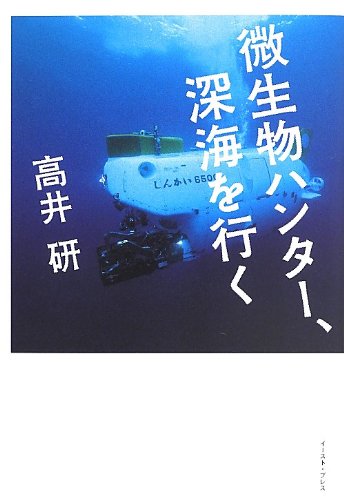

©︎ JAMSTEC

ー

After joining JAMSTEC at age 27, you earned worldwide recognition as a researcher for a series of studies.

Mr. Takai

The research I wanted to do was to go and find the microorganism known as the Last Universal Common Ancestor, or “LUCA,” in deep-sea hydrothermal systems. After I managed to discover something of the sort and published a paper on it, my name became internationally known. I was in my early to mid 30s. From that point on, I felt much more self-assured as a researcher.

So, your conscious decision to tackle research that no one else was doing was a fruitful one.

Mr. Takai

Yes. The fact that no one had come before me was good. At the time, I had only one supervisor, Dr. Koki Horikoshi (former director-general of JAMSTEC’s Extremobiosphere Research Center), who never interfered with my research at all. He only asked that I write an interesting paper, which was great. This allowed me to pursue research that brought me closer to my goal of understanding the origin of life.

Researchers often say that at a certain point in their career, they “fall in love again” with the subject they study. They feel, “Wow, this is really amazing.” How did it go for you?

Mr. Takai

This happened to me at the age of 35 or 36. I often describe it as a feeling of “enlightenment.”

You attained awakening!

Mr. Takai

It really was like that (laughs). As I went around the world to study hydrothermal systems, I realized that the rock formations, geology, chemistry, physics, and other conditions that underlie hot springs are tied up with the microorganisms that live there. I also saw that systems are organized based on the interrelationships between conditions.

At that moment of realization, I felt a deep internal conviction that this was a general rule that applied to the whole universe, not just the Earth. I felt like I could draw a mandala to represent the law. I can only describe this insight as a kind of enlightenment. It would take me 10 years to write a paper on my realization, but in my mind, I had already made the connection. So, the belief came first; then later I was able to substantiate it.

As one enzyme researcher put it, there are moments when you glimpse that a variety of phenomena are interconnected, including things that move the world. The most delightful moment is when numerous new possibilities become apparent after a realization.

Mr. Takai

When I started working at JAMSTEC with people from around the world and with experts in various disciplines from around Japan, my knowledge of different fields—not just microbiology and biology, but also geology and geochemistry—clicked and aligned inside me. That was the sensation I felt. That was one of the cool things about coming to JAMSTEC.

©︎ JAMSTEC

ー

What kinds of twists and turns did you go through before deciding to explore the origin of life as a research theme?

Mr. Takai

When I was in the fourth year of elementary school, my family moved from the city of Kyoto to the countryside of northern Shiga Prefecture. Basically, my playgrounds became the local rivers and lakes. Moving from a crowded urban district to a sparse natural environment made me realize what a puny presence humans have in the “big picture” of nature. Even while at elementary school, I began to get a sense of the umwelt, or “self-centered world,” as it is called in ecology; the sense that humans are a small part of a big world.

However, I was not really into science, so the mysteries of nature didn’t captivate me. It’s just that biology was all the rage, so I thought, “If I can make a name for myself in this field, I could become the best in the world.” I was fascinated by the origin of life because it was the number one question in biology.

In a book, Susumu Tonegawa (a biologist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) wrote that one of the unfortunate things about biologists is that they get hung up on boring problems. He said that he found all problems interesting and fun to tackle. According to him, the important thing is finding a grand goal that needs to be attained; rather than worrying about how boring or interesting a problem is.

I felt this to be very true. I thought, “If I’m going to do this, my work will only have real value if I tackle a big problem that I can spend a lifetime solving. I therefore set myself the goal of uncovering the origin of life; something that human beings have been unable to do for thousands of years. It was my ambition that led me to take up this theme.

You remind me somewhat of an explorer, like Indiana Jones!

Mr. Takai

I do think of myself as a kind of explorer. In any event, I wanted to be the first do something important. In terms of mindset, a researcher is a bit like an entrepreneur who launches venture businesses. As a researcher, you can make all your own career decisions. You can take risks and live your life any way that you envision it. I can asure you that a researcher is a wonderful profession.

ー

Earlier, you said that it took you many years to love the ocean after becoming a researcher. Was there anything that specifically triggered this change?

Mr. Takai

After joining JAMSTEC, I took an opportunity to study abroad for a year. I was studying underground microorganisms at a facility in the desert in the U.S. As I lived in an environment surrounded by sand, I was constantly nagged by a feeling that something was missing.

Then, one day, as I rode on a ferry and looked out at the sea, I was suddenly struck by how wonderful it was. I realized for the first time that I really loved the sea. If I hadn’t been in a desert environment, maybe I wouldn’t have felt such a longing for the sea. I vowed that from that day on, I would spend the rest of my life to studying the deep sea. That’s what triggered my devotion to deep sea research.

It can happen that you only realize you really love something when you are in a totally different environment or situation.

Mr. Takai

That is probably a good way to find out what you really like. That’s why I don’t advise young people to go straight into research just because they “love insects” or “love living things.” I suggest that they reflect seriously on whether they really love those things or not.

The realization that I really loved something that I hadn’t previously liked made me feel a strong determination not to give that thing up for the rest of my life. Until then, I didn’t value research or the ocean very deeply. After my realization, everything changed.

Sometimes I talk with researchers about what would happen if enzymes disappeared from the world. A thought experiment to try and imagine life without enzymes.

Mr. Takai

That’s interesting. Certainly, if people reflected on life without the things that they currently take for granted, they would appreciate the importance of those things.

Dr. Takai’s words on the importance of observations in the field were very persuasive. Part 2 begins with a discussion on two viewpoints on the nature of life and includes a detailed explanation of the theory that the origin of life on Earth lies in deep-sea hydrothermal systems. We even talk about the possible existence of enzymes in outer space. It is a discussion rich in imagination and romance.

→ Continue to Part 2Enzymes are active in every aspect of our world, and we are seeking new possibilities for them.

In this corner, we visit people who are currently active in various fields with "Enzo" and ask them about their stories.